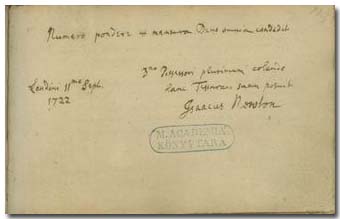

Numero pondere & mensura Deus omnia

condidit. *

D[omi]no Possessori plurimum colendo hanc

Tesseram suam posuit

Isaacus Newton

Londini 11mo Sept. 1722

|

|

God hath ordered all things in measure and number and weight. *

I recommend this motto of mine to the much

respected possessor [of this book].

Isaac Newton

In London, on September 11, 1722.

|

p.

109. London, September 22, 1722

Newton, Isaac, Sir Newton, Isaac, Sir

(1643-1727), English physicist,

mathematician, astronomer

Isaac

Newton was born on January 4, 1643 in Woolsthorpe Manor near

Grantham in Lincolnshire. In England, where the Julian calendary

was still observed, this day fell on Christmas, December 25. His

father, Isaac Newton died at the age of 36, three months before

the birth of his son. His mother Hannah Smith married again and

moved to her husband's town. Isaac's grandmother stayed in

Woolsthorpe Manor, and took care of him. In 1655 he was sent to

the grammar school of Grantham, but after the death of his

stepfather his mother called him home to work in the manor.

However, his uncle and the rector of the school managed to

convince her to let him back to school. He lived at the town's

pharmacist, and already at this time he prepared curious

instruments, small mills and water-meters. In 1661 he went to Trinity

College in Cambridge, where he read mathematics and philosophy.

During the plague years of 1665-66 the college was closed, and

Newton went back to Woolsthorpe. Here he made his great

discoveries, the differential and integral calculus, the theory of

colours, the laws of dynamics, as well as the law of universal

gravitation, but at this time he did not publish either of them.

In 1667 he became fellow of the College, and in the following year

Master of Art. In this year he prepared his first mirror

telescope. In 1669 his professor Isaac Barrow (1630-1677), himself

one of the forerunners of differential calculus, resigned, and

gave his post to his brilliant student. Newton began his lectures

on optics in the Trinity College in 1670. In 1672 he was

elected a member of the Royal Society of London; he demonstratd

his telescope, and presented his first treatise on the theory of

light and colours. However, the disputes following thereafter,

principally the sharp criticism of Robert Hooke prevented him from

publishing his results. Hooke also accused him of having stolen

his recognitions on the interpretation of the movement of the

planets. Finally, through the reconciling intervention of Edmond

Halley, and with his financial support and stimulation in 1687 he

published one of his chief-d'oeuvres: Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica,

treating the laws of dynamics and general gravitation. In this

topic he also had correspondence with Richard Bentley, the future

Master of Trinity College. In 1697 he was sorely tried by the

death of his mother. He also continued to support the family of

his half-brothers. In 1692 he fell in a deep exhaustion, and he

completely retired from scholarly work for two years. In 1689 and

in 1701-1702 he represented the University of Cambridge in the

Parliament of London. In 1696 he became Warden, and from 1699 the

Director of the British mint. He moved to London, and from 1703

until his death he was President of the Royal Society. In 1704

he published his second chef-d'oeuvre, the Optics, on the

nature of light. In 1705 he was knighted by Queen Anne for his

scholarly merits, as well as for his efforts done in the Mint.

His unfortunate dispute of precedence with Leibniz

had begun some years earlier, and it left him no peace neither

after the death of Leibniz: it embittered all his life, caused a

great harm to the development of mathematics, and especially in

British scholarly life. The German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

discovered parallel with Newton the differential and integral

calculus, and he published his results in 1684 and 1686. Newton

had arrived to these same recognitions earlier, but he spread them

only in a narrow circle, and published them only in 1704, in two

articles connected with the Optics. The notation introduced

by Leibniz is simpler and more uniform. The merits of both are

indisputable. The basic theorem of mathematical analysis

expressing the connection between differential and integral

calculus is today called Newton-Leibniz-theorem.

Sir Isaac Newton

founded no family. He died on March 31, 1727 (according to the old

calendar, on March 20), and was buried in Westminster Abbey. His

long Latin epitaph gives an account of his scholarly merits [Jöcher III 891].

His two most important works are the Philosophiae

naturalis principia mathematica. London, 1687. Mathematical

Principles of Natural Philosophy. London, 1729. – Opticks,

or, a treatise of the reflexions, refractions, inflexions and

colours of light. Also two treatises of the species and magnitude

of curvilinear figures. London, 1704.

Newton was extremely respected and legends

circulated about him already in his life. Even in later times anecdotes were

made on his modesty and distractedness, that obfuscate reality to

some degree. The literature around his personality and scholarly

achievements amounts to a whole library. Even Voltaire belonged to

his popularizers. Today every schoolboy knows the name of Newton.

If one has a single look at a lexicon of natural sciences, or an

index of a handbook of mathematics or physics, will suddenly find

a handful of expressions or theorems beginning like

“Newton's…”: and continuing like binominal theorem, liquid,

ring, law of cooling, alloy, telescope… The unit of force

in the SI (Système Internationale) has borrowed his name: it is

called newton, and abbreviated as N. All the achievements of

Newton had their foundations in the thoughts of his forerunners,

Galilei, Kepler, Descartes and others, but he (and Leibniz in the

field of mathematics) organized these into unified theories. He

indicated new directions in scholarly and philosophical thought,

like that white light can be decomposed into colours, that force is

needed not to maintain movement, but to change it, that celestial and terrestrial phenomena (weight of

bodies, ebb and flow, the movement of the moon and of the planets)

obey the same laws, that one has to base his theories both on

experience and thought. The 17th century, “le grand siècle”, was

the century of genius. Newton himself wrote to Hooke in 1676: “If

I have been able to see further, it was only because I stood on

the shoulders of giants.” He was right, but only a Newton

was able to step on the shoulders of the giants. Trinity

College of Cambridge still keeps some of his personal objects and

manuscripts. His statue there bears the inscription from

Lucretius: Qui genus humanum ingenio superavit.

Isaac Newton choose a motto really fitting to

himself from the Bible, one written eighteen centuries earlier by

the Jewish philosopher of Alexandria: Thou [God] hast ordered

everything in measure and number and weight. – Edmond Halley has

noted in the Album of Páriz Pápai in 1716 in Oxford (p.

237).

•

BritHung • DNB • Filep • Jöcher • Jöcher-Adelung • MNL •

Newton-Fehér • Newton-Heinrich • Newton-web • Simonyi • Vekerdi |