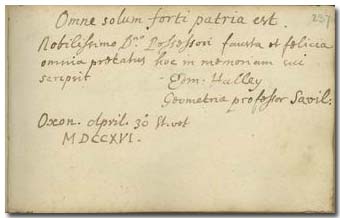

Omne solum forti patria est. *

Nobilissimo D[omi]no Possessori fausta et foelicia omnia praecatus

hoc in memoriam sui scripsit

Edm[undus] Halley

Geometriae professor Savil.

Oxon[iis] April. 30º st[ilo] vet[eri] MDCCXVI.

|

* Ovid, Fasti 1.493: “omne solum

forti patria est, ut piscibus aequor”.

|

|

|

Every land is homeland for the strong. *

I wish all kind of happiness and good fortune

to the owner [of this album], recommending myself into his memory

Edmund Halley

Savile Professor of geometry

In Oxford, on April 30, 1716, by the old calendar

|

p. 237. Oxford, May 11, 1716

Halley, Edmond

(1656-1742), English astronomer and

mathematician

Edmond

Halley was born on November 8, 1656 (by the old calendar, on October 29)

in the village of Haggerston near London (Shoreditch), the

son of the rich soap-maker Edmond H. He studied in St. Paul’s

School in London, and from 1673 in Queen's College Oxford. At that

time he already mastered Latin, Greek and Hebrew, and took

astronomical measurements and calculations. Some times he visited

in Greenwich the royal astronomer John

Flamsteed (1646-1719) who was working on a new catalogue of stars

on the basis of the most exact measurements of the period. This

intrigued Halley, who proposed to do similar measurements also on

the southern hemisphere. In November 1676 he broke his studies,

and with the financial support of his father and with letters of

recommendation of King Charles II he sailed on a ship of the East

India Company to the island of St. Helena, the southernmost point

of the British Empire on the Atlantic. In spite of wrong weather

he managed to determine the exact coordinates of 341 stars, to

observe the transit of the Mercure in front of the Sun, and to try

pendulum experiments. He set off for home in January 1678, and at

the end of the same year he published the first catalogue of

southern hemisphere stars. At this time he received M.A. degree on

royal command, and in November he was elected member of the Royal

Society. From 1713 he was the secretary of the Society, after

having edited its Transactions between 1685 and 1693. It

was in 1684 the first time he visited Newton in Cambridge. At that

time the problem of the movement of planets stood in the forefront

of interest. The laws by Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) were already

generally acknowledged, and now three members of the Royal

Society, Halley, Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723, builder of St.

Paul's Cathedral in London) and Robert Hooke (1635-1703,

discoverer of the law of elasticity bearing his name) parallelly

researched the force keeping the planets in their orbit; Wren even

set a prize for the solution of the question. Hooke and Halley had

already calculated that the force was inverse to the square of the

distance between the planet and the Sun, but could not conclude

the orbit of the planet. At the visit of Halley to Newton this

latter disclosed to him that he had already achieved a

mathematical proof that the orbit concerned was elliptical.

Encouraged by Halley, Newton exposed his theory in his great

oeuvre, the Principia, cured and published by Halley in

1687 on the commission of the Royal Society and on his own costs,

also settling the dispute of precedence between Newton and Hooke.

In 1686 he prepared a map of the world showing the prevailing

winds over the oceans. It has the distinction of being the first

meteorological chart to be published. In 1693 he published the

mortality tables of the city of Breslau (Wrocław), in which

he was the first to attempt to relate mortality and age in a

population. In 1698-1700 he sailed to the southern part of the

Atlantic, and on the basis of the measurements by himself and

others in 1701 he published the first charts of the variation of

the compass in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, giving the first

charts with lines of equal declinations plotted. In 1704 he was

appointed Savilian Professor of the chair of geometry at the

university of Oxford. (Sir Henry Savile (1549-1622) was a scholar

of ancient science, a traveller and the Greek professor of Queen

Elisabeth I; he founded the chair of geometry and astronomy in

Oxford in 1619.) Halley here translated from Arabic to Latin a

text by Apollonius, and reconstructed his lost books on the basis

of Pappus; he also edited Ptolemaeus and other ancient authors. In

1705 he deduced from the Newtonian laws of cometary orbits that

the comet appearing in the years of 1531, 1607 and 1682 is one and

the same, which will return the next time in 1758. It was in fact

observed at the end of 1758 with a perihelium in March of 1759.

This comet was later named after Halley; its period of revolution

is about 76 years, recurring in 1835, 1910, 1986 (its next return

is waited for 2062). In February 1721 Halley succeeded Flamsted as

Astronomer Royal. He died in Greenwich on January 14, 1742, and

was buried in the nearby Lee, in a common tomb with his wife Mary

Tooke (?-1737). His great merit was to have uderstood the results

of Newton, and also applied them on the movement of the comets; to

have published the Principia by Newton; and to have tested

the new scientific data in the practice, for example in

navigation. Some of his most important works are: Catalogus stellarum

australium … London, 1679. – An estimate of the degrees

of mortality of mankind drawn from curious tables of the births

and funerals at the city of Breslaw. London, 1694. – The

description and uses of a new and correct sea-chart of the whole

world, shewing the variations of the compass. London, 1700. -

Astronomiae cometica synopsis. London, 1705.

Halley in his note written in the album of Pápai Páriz indicates

his title of Savilian professor of geometry. Isaac Newton had

also made his note in the album of Ferenc Pápai Páriz on p.

109.

•

BritHung • DNB • EncBrit • Jöcher-Adelung • Michaud • MNL • Savile |